Pipelines for Protein Engineering

Thoughts from a Protein Engineering PhD student

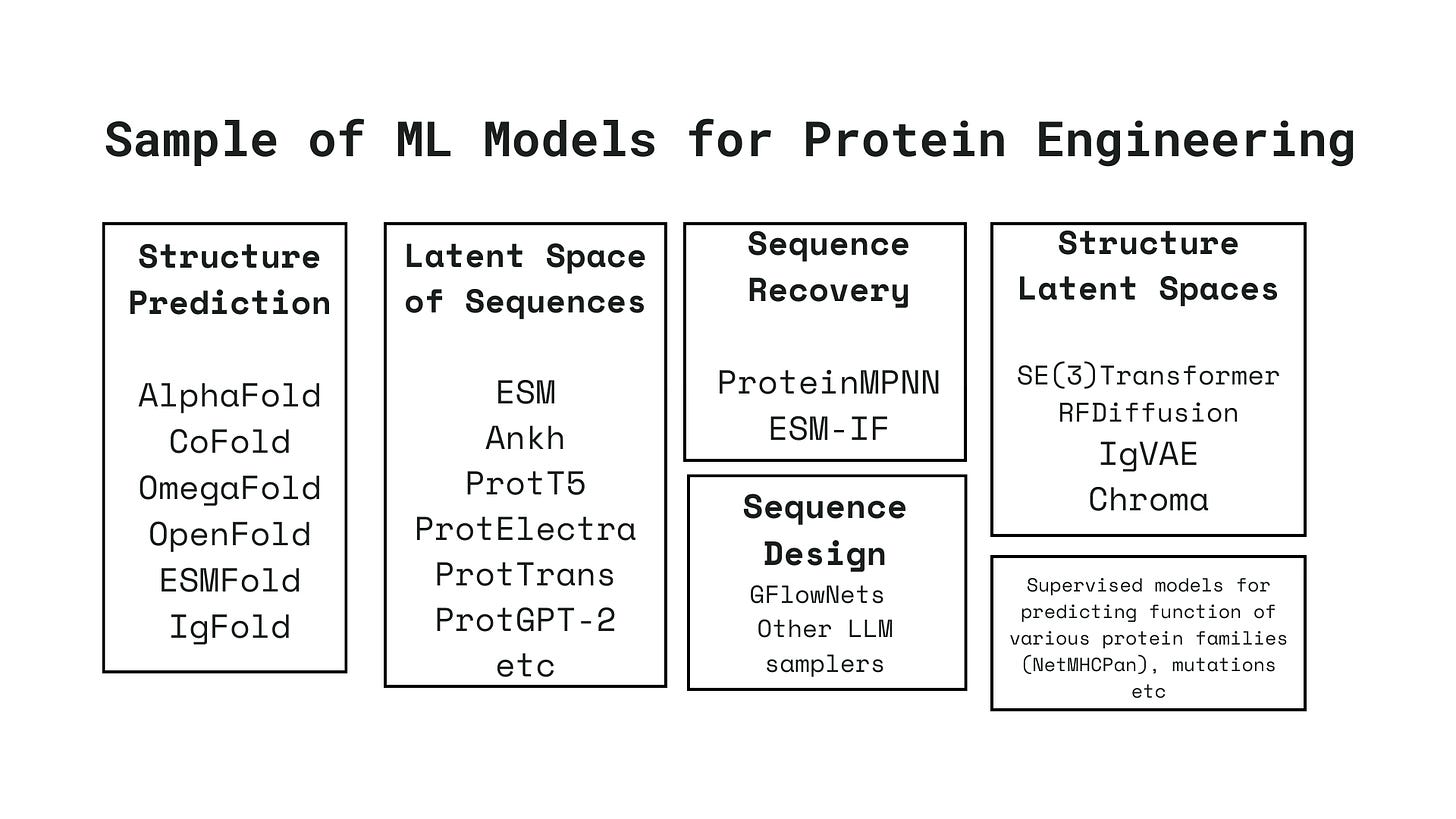

In recent years, there has been an explosion of machine learning models that offer insights into the landscape of protein sequences and structures. Often, these models are specialized in performing one of the various tasks involved in a protein engineering pipeline, such as protein structure prediction[2], protein-protein interactions[5], protein-ligand interactions[7], sequence recovery[1], and many more. All of these models provide valuable insights into how proteins function and interact.

However, the complexity of biology, coupled with the limited availability of datasets and suitable metrics for filtering designed proteins for desired function or property, underscore the necessity for developing efficient pipelines aimed at generating intelligent libraries for protein design. We also need better benchmarks to determine the suitability of these tools for various protein engineering challenges beyond the problem of designing drugs/binders.

I have been fortunate enough to collaborate with biologists focused on engineering various protein families in the lab. These collaborations have allowed me to delve into the creation of intelligent pipelines using these tools, and exploring the limitations of these models. Through a series of upcoming blogs like this, I am hoping to thoroughly examine these challenges. I intend to assess the feasibility of addressing them using existing models and identify areas where limitations exist and hopefully prompt the exploration of new research directions.

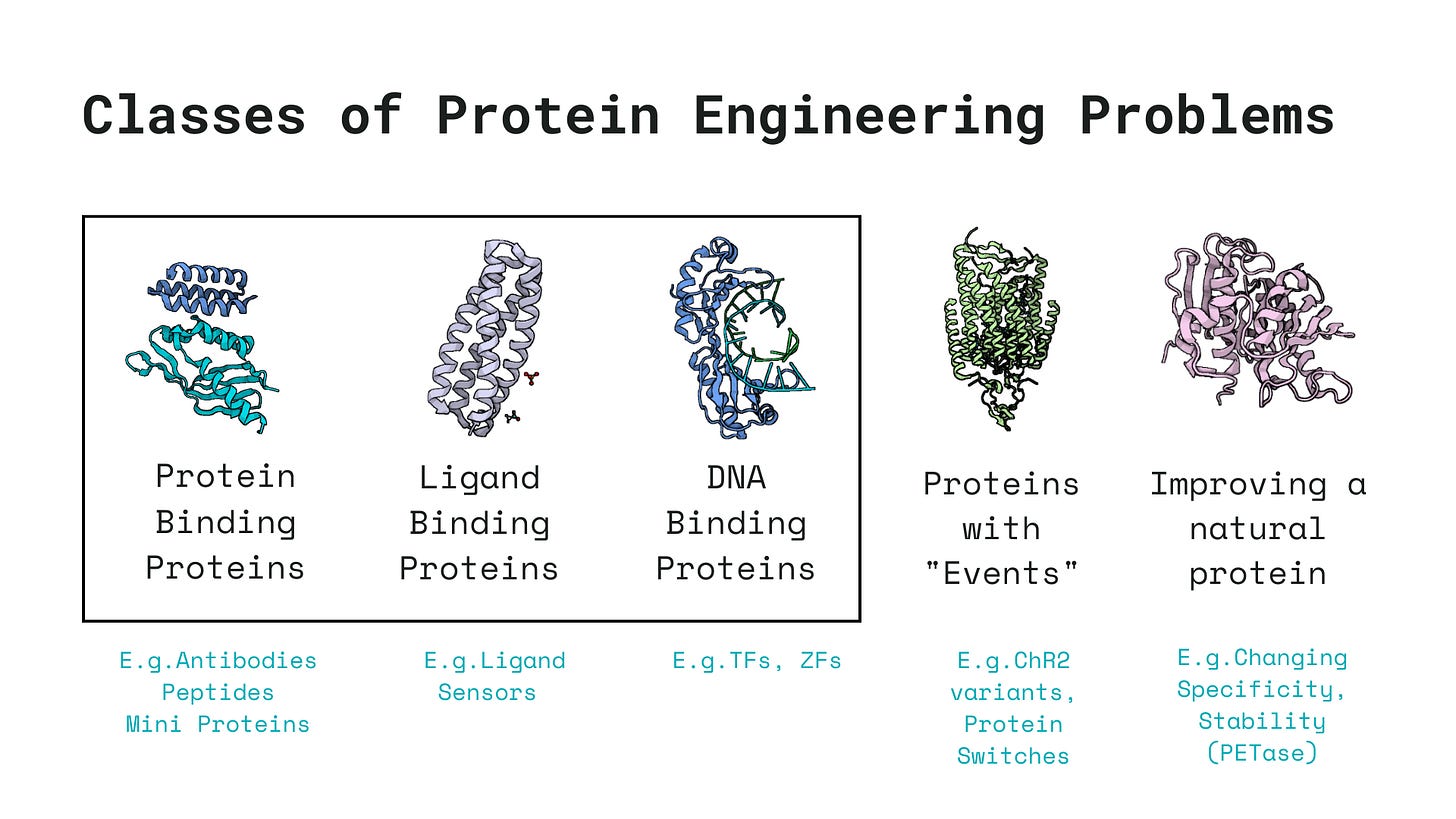

Whenever I embark on trying to engineer a new protein, I try to fit the problem into one of these 5 classes of protein engineering problems to determine what the machine learning pipeline should look like and whether machine learning can even be used for engineering these family of proteins.

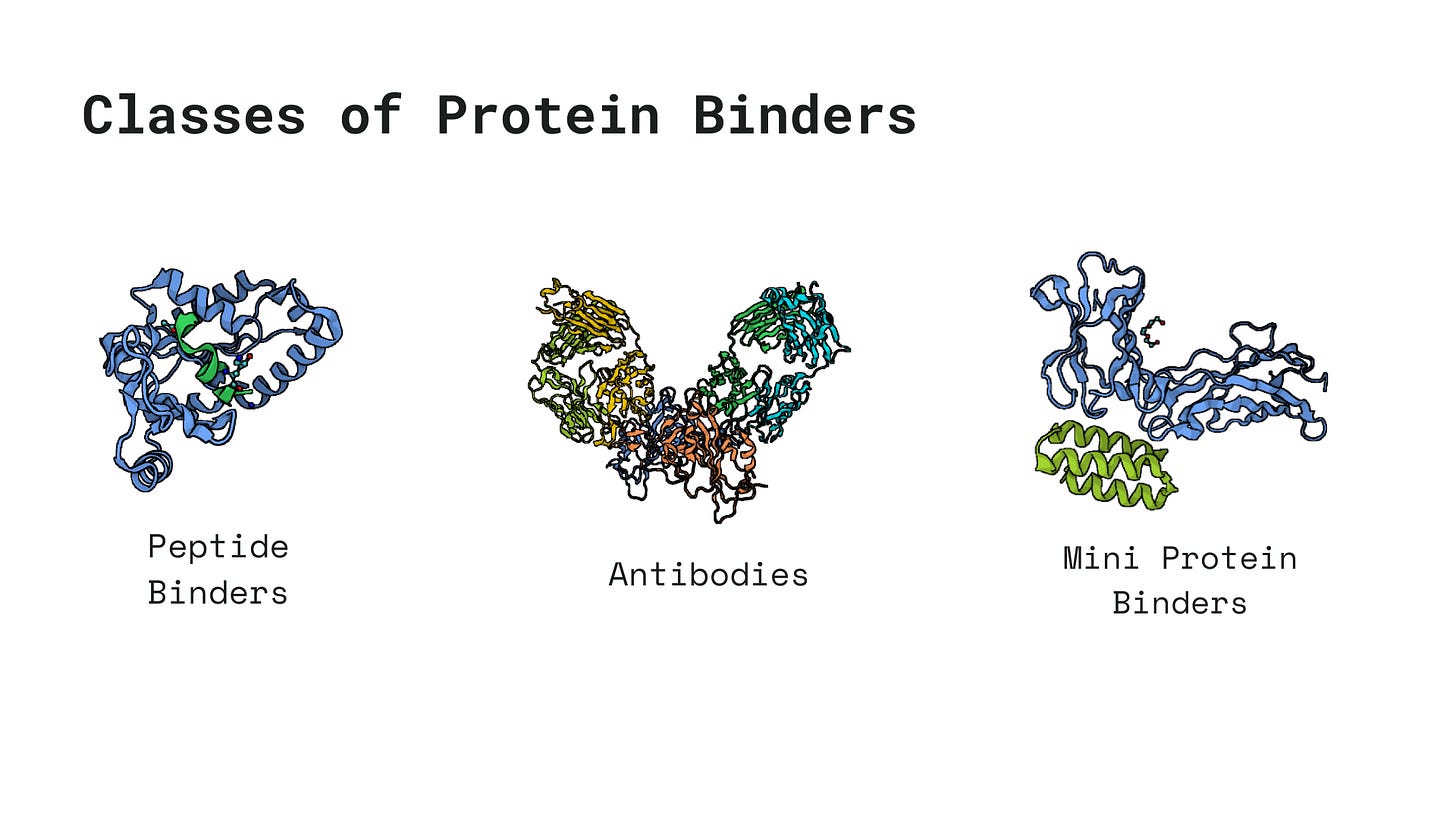

Much of protein engineering pipelines usually revolve around the goal of designing proteins tailored for specific binding events, such as binding to DNA, small molecules, or other proteins. These binding agents generally fall into one of the following three categories, chosen based on a variety of factors including delivery feasibility, immunogenicity, binding affinity, etc.

Pipelines for designing protein binders vary vastly based on whether you are trying to engineer a peptide or a antibody or a mini-protein. In this series of blogs, we will be exploring what a state of the art pipeline would look like for each one of these class of proteins and what their limitations are. This post is going to focus on the Step 1 of any protein engineering pipeline.

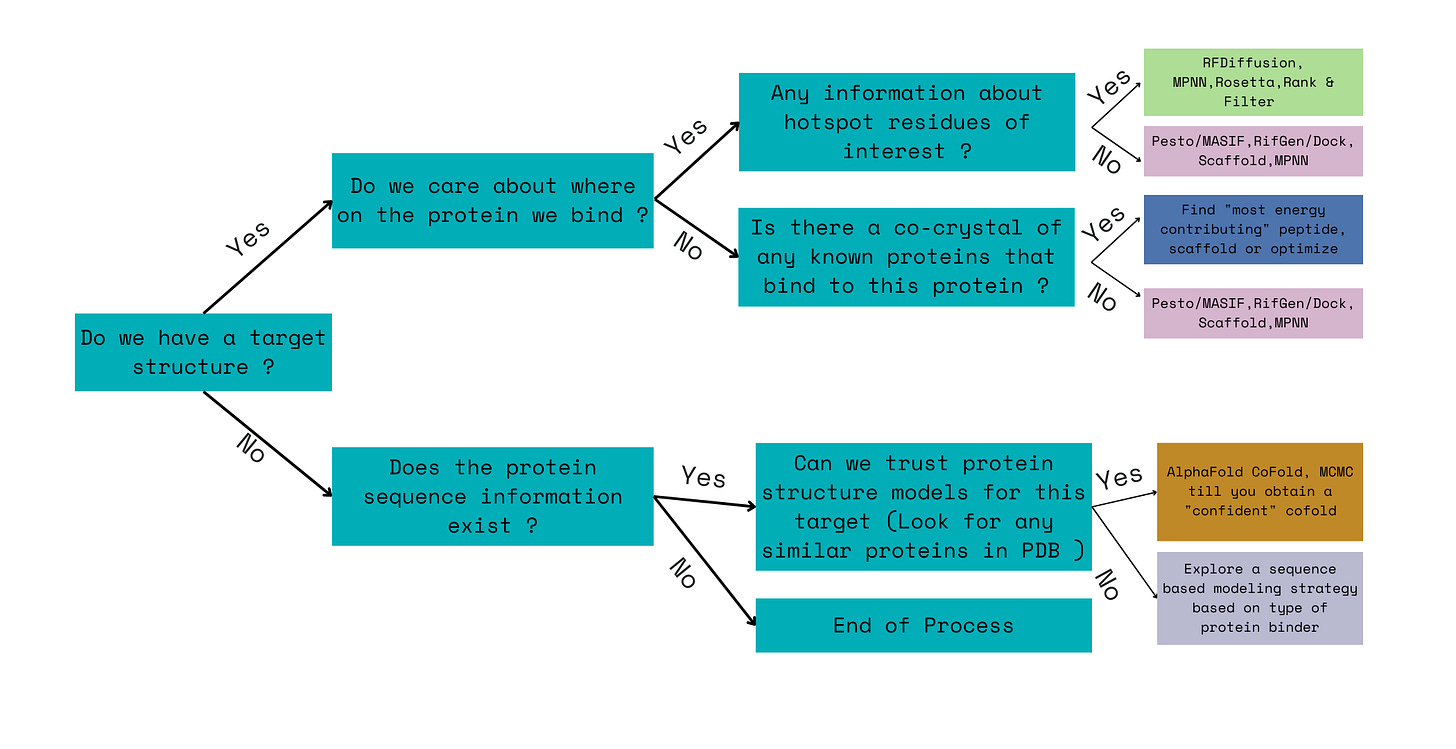

The Step 1 in engineering a pipeline for designing a binder or any protein in the above five classes of protein engineering, often starts with information mining about a target. The following flow chart is a sample of decisions that a protein engineer would have to make before building a ML pipeline.

First step is looking up to see if there is a crystal structure of the target. Then, we can look for any information about potential hotspots or active sites we can bind to on the protein surface. If that information exists, then we can use RFDiffusion,MPNN etc to design binders - We will explore this pipeline and it’s limitations in the next post on Step 2. If not, then we can look for any known co-crystals in the PDB. If there is a co-crystal, we can extract information about the fragment that contributes the most ddG for that binding interaction. If no such co-crystal exists, we might try to use models based on geometric features of the protein structure like Pesto[4] to identify potential hotspots. If there is no known crystal structure in the PDB, we have to explore whether we can trust AlphaFold predictions of target sequence’s structure. If we can trust AlphaFold predictions we can use this with Alphafold cofold or multimer to optimize a random sequence till we get a confident “co-crystal” prediction. If we can’t trust the AlphaFolded structure or if the structure is disordered or loopy then we have to rely on sequence based models alone.

This is the step that typically consumes most of my time. It often involves extensive literature search and review to find information regarding potential hotspots, conserved sites on the protein, active sites, and any details about existing binders/co-crystals. When it comes to repurposing proteins that exhibit binding to small molecules or DNA, it involves a similar review of existing literature to uncover any insights regarding potential functional sites, mutations, etc.

This is a step where LLMs could potentially be used by protein engineers, to distill important information from research publications like automatically identifying potential functional sites, effects of mutations at specific sites on function across diverse protein families etc. Furthermore, by integrating interpretability and explainability into protein machine learning architectures, we can leverage models to discover potential important sites on proteins for specific function or property.

Please subscribe if you are interested in getting notifications for the next post on Step 2: Designing binder libraries using structure based models for protein design.

[1] Dauparas, J. et al. Robust deep learning–based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science 378, 49–56 (2022).

[2] Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

[3] Gainza, P. et al. Deciphering interaction fingerprints from protein molecular surfaces using geometric deep learning. Nature Methods 17, 184–192 (2019).

[4] Krapp, L., Abriata, L. A., Rodríguez, F. C. & Peraro, M. D. PeSTo: parameter-free geometric deep learning for accurate prediction of protein binding interfaces. Nature Communications 14, (2023).

[5] Stärk, H. EquiBIND: Geometric Deep Learning for Drug binding Structure Prediction. arXiv.orghttps://arxiv.org/abs/2202.05146 (2022).

[6] Jain, M. Biological Sequence Design with GFlowNets. arXiv.org https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.04115 (2022).

[7] Corso, G. DiffDock: diffusion steps, twists, and turns for molecular docking. arXiv.org https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.01776(2022).

[8] Watson, J. P. et al. De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature (2023) doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06415-8.

Nice, Manu! I liked this landing point for the first post: "This is a step where LLMs could potentially be used by protein engineers, to distill important information from research publications like automatically identifying potential functional sites, effects of mutations at specific sites on function across diverse protein families etc." Sounds obvious once I read it, definitely curious where the state of the art is with efforts like that